Congress in recess, but negotiations continue on BBB, avoiding a February government shutdown

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi won a Supreme court victory early Monday, when the Supreme Court turned away Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy’s bid to invalidate proxy voting, the system of voting that the House adopted in 2021 as a pandemic safety measure. Dozens of lawmakers, including plenty of Republicans who had signed onto McCarthy’s complaint, have used the process which allows members to cast votes without being physically present. Like Rep. Elise Stefanik, the GOP Conference Chair from New York. Last Thursday she told reporters, “We believe in in-person voting. When Republicans win back the House, that’s what we are committed to.” Stefanik had her first child last year, and voted by proxy in the week that followed.

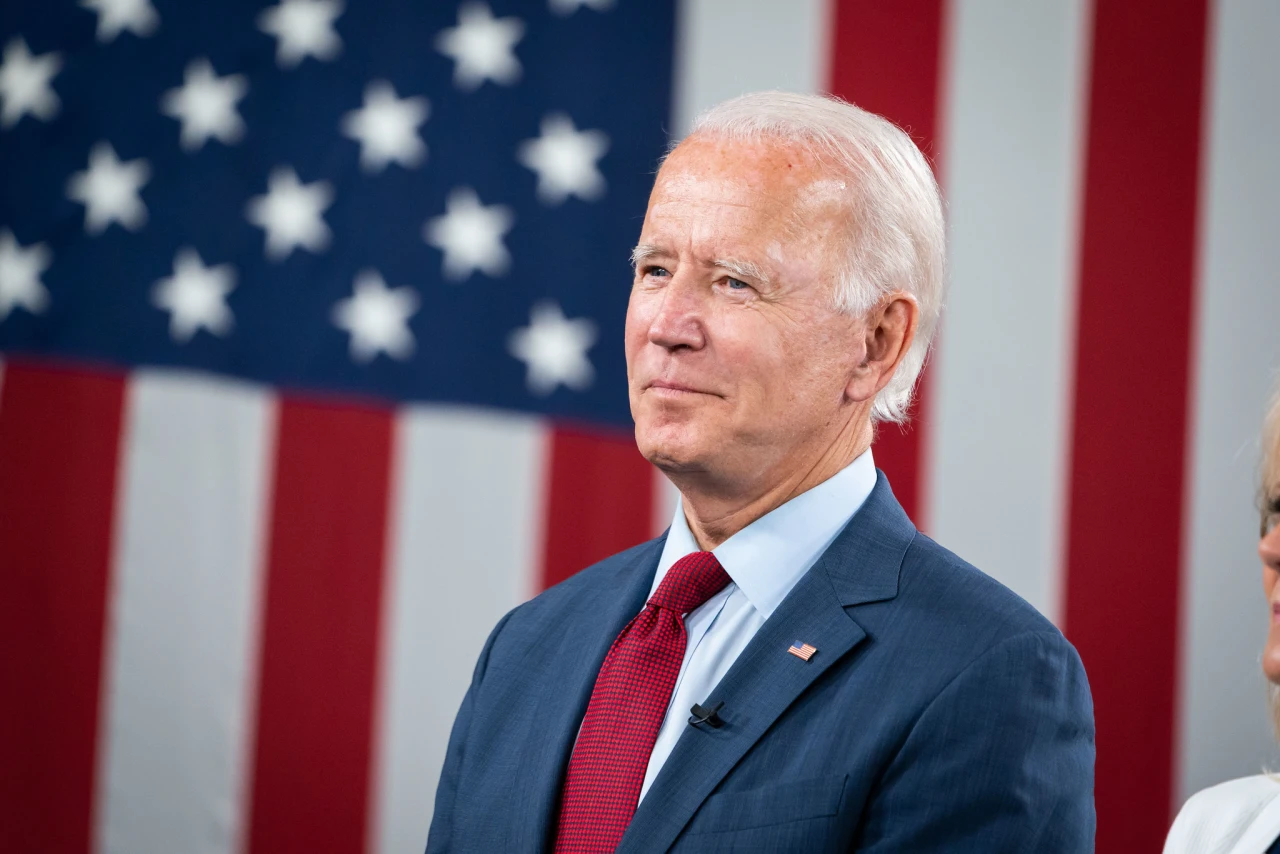

Not that the House will be using that, or any voting process, this week. Both House and Senate are out for the week for a delayed Martin Luther King Jr. Day recess. After last week’s discouraging Senate attempt to break the filibuster to save democracy, thwarted by would-be presidents Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, both chambers will turn to two big projects. First, they have to figure out fiscal year (FY) 2022 spending and get an omnibus spending bill passed by Feb. 18, while also determining how they can move forward with President Biden’s Build Back Better (BBB) plan after it was derailed by Manchin (again) in December.

For the past year, the first year of Joe Biden’s presidency, the government has been operating under a Trump budget. That’s how Republicans wanted it, and what they’ve been able to achieve so far by refusing to allow a new set of appropriations bills to pass. Instead, the government’s operated on continuing resolutions, the short-term spending bills that continue operations from the last spending bill to pass.

The only opportunity that the Biden administration has had to push its agenda was in the massive American Rescue Plan COVID relief bill, and that was great but limited in what it could achieve. That’s left most agencies of the government continuing to operate under Trump-forced cuts, struggling under years of austerity. Biden’s administration saw the problem, and in its budget request for FY22, added across-the-board increases, up to as much as 40% over previous levels.

That’s happened in large part because Biden and Democratic leadership put all their eggs into the infrastructure and BBB basket starting back in April. Biden thought he could use the momentum of the success of ARP and bring enough Republicans along on his plans. He spent months in pursuit of that, first allowing the hard infrastructure bill to be split from the social infrastructure and climate measures, and then talking House Democrats into passing the bipartisan hard infrastructure bill with the promise that he had BBB well in hand and would bring Manchin along.

That consumed pretty much all of the energy Congress—mostly the 50-50 deadlocked Senate—had for the past year. A couple of weeks ago, appropriators in both chambers said they were making progress in coming up with a deal. Senate Chair Patrick Leahy and ranking Republican Richard Shelby had a tentative agreement on the framework for the legislation, reportedly, and the “Four Corners”—the top Democrats and Republicans on the committees met. “The four of us had constructive talks of where we go and how we get there and how we start,” Shelby told reporters. “We hadn’t worked that out yet.”

That, again, was two weeks ago. Last week was taken up—appropriately—by the voting rights push, but negotiations are presumably continuing with staff during recess. There’s real pressure to get that done from numerous sides. Colleges and universities are scrambling to come up with financial aid packages while Congress debates a $400 increase to Pell Grants. They should be wrapping up and sending out financial aid award letters now, but don’t know whether they’ll have that Pell Grant increase or not. It’s also critical for the students, many of whom were able to enroll because of the help provided under ARP, but with that money spent, might have to drop out.

“A year and a half ago, we were dispensing money hand over fist,” Christina Tangalakis, associate dean of financial aid at Glendale Community College in California, told the Post. “The government positioned us as this place where a student could get relief. And now that’s dried up, and they’re delaying the Pell Grant increase. A student who may have just begun to build trust in us, where are they at now?”

On the other side, defense contractors and trade groups are getting antsy, wanting to make sure that the generosity they saw from the House in the initial defense spending bill carries through. Remember, the House passed a $768 billion bill, $28 billion more than the Pentagon even requested. Pressure from that group could be enough to get Republicans serious about getting a bill done by the Feb. 18 deadline. It’s also countervailing pressure against their desire to keep Biden hamstrung with Trump’s budget—the defense groups are screaming that inflation is going to break them.

Leadership in the House is also considering whether to include additional COVID relief in the spending package. “We are working very closely with [Appropriations Chair] Rosa DeLauro on the omnibus bill,” Pelosi told reporters last week. “I had thought that it could be possible for us to do a Covid relief package within that bill but fenced off as emergency spending so it doesn’t take away from our other domestic non-discretionary spending.” If they do, it is likely to be additional aid to businesses rather than individuals.

There should be some clarity by the end of this week on how the omnibus is coming together, though negotiations could again go right down to the wire. Flirting with government shutdowns is just how the 21st century Congress operates. The outlook for BBB, voting rights, and all the other emergencies is much murkier.