Obamacare opens for 2022 enrollment, with potential enhancements in Build Back Better

It’s open enrollment season for the Affordable Care Act again, and if you’re thinking, “How could that be? It just ended,” you’re right. The Biden administration extended the enrollment period into the summer in order to help all those affected by the pandemic. The Biden administration is also reversing the Trump tradition of limiting the enrollment period, and it will run from Nov. 1, 2021 through Jan. 15, 2022. However, to have coverage that takes effect as of Jan. 1, people will have to enroll by Dec. 15.

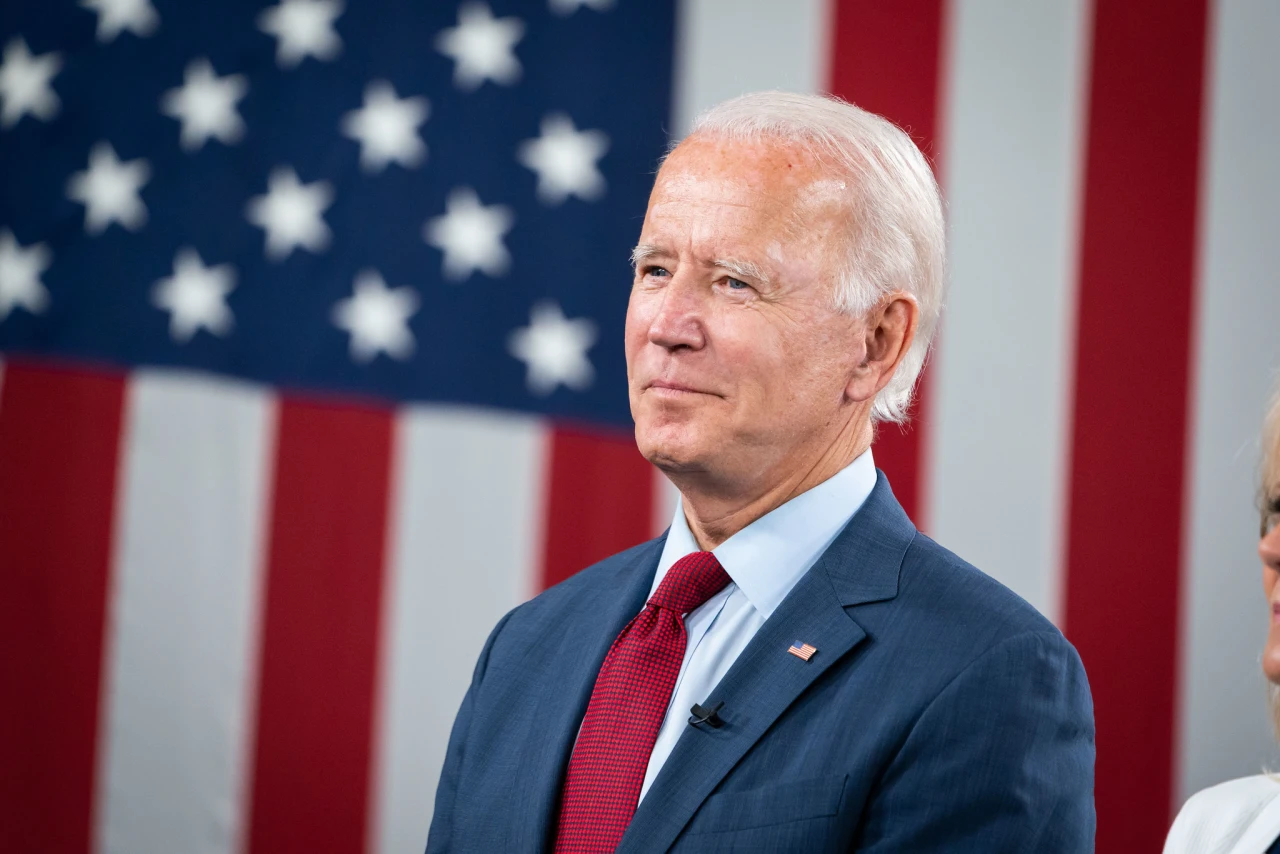

Premiums for 2022 will be about 3% lower than this year and there will be more insurers offering more plans. On the whole, there will be more and cheaper options for most everybody, and because of that people who are renewing coverage should go shop for the best deals. They’ll also benefit from more assistance if they need it—President Joe Biden is restoring the funding the former guy slashed for outreach and assistance through the Navigator program.

If the Build Back Better Act being negotiated now in the House passes, and the Senate passes it as well, there will be more ACA changes and big changes in a few discreet parts of the ACA and health care in general. Some of those elements aren’t clear yet: Medicare expansion to include hearing, dental, and vision care and drug price negotiating are still being worked out.

One key ACA expansion that has been a point of contention for Democrats is Medicaid expansion to the people in the gap—the red state citizens whose lawmakers have deprived them of the program. That’s about 2 million people, and for Democrats like Sen. Raphael Warnock in Georgia, a key priority. Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia has opposed it because he views it not as helping those low-income workers, but as a “reward” for the states that haven’t expanded. In response, his colleagues have worked on a plan that he should like—it basically rewards health insurers by giving them more customers, but at the same time extends coverage to this group.

Those in the Medicaid gap live in the dozen states that haven’t expanded Medicaid. They earn incomes that are too low to qualify for subsidies on the ACA exchanges (which begin at 100% of the federal poverty line), but are too high for traditional Medicaid. Lawmakers originally talked about essentially putting a limited public option for this population on the exchanges, but Manchin balked. So now lawmakers have come up with a plan to expand the subsidies on the Obamacare markets to the low-income adults in those states through 2025. The bill would also punish non-expansion states by reducing payments they get in Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital payments and federal funding for uncompensated care pools—the two programs that care for the uninsured. That theoretically wouldn’t hurt the low-income people or the hospitals in those states, because they would now have private insurance to cover their care.

Speaking of Medicaid, the bill makes a serous effort to help low-income mothers, who are disproportionately people of color, by providing health coverage for new moms for a full year after giving birth.

The bill also extends the bump-up of ACA subsidies that was first passed in the American Rescue Plan earlier this year. Under that expansion, people making more than 400% of the federal poverty level—about $52,000 per year for an individual—became eligible for Affordable Care Act subsidies. That program was supposed to expire in 2023, and this bill extends it through 2025. People who make below 400% of the poverty line will continue to get more generous subsidies as well. This is part of what makes those new plans so much more affordable this year.

Slipped into the bill is language to permanently fund the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and to require states to keep children in the program for a full 12 months even if the household income rises above the eligibility level for the program during the 12-month period. Families at this income level often teeter in and out of qualifying for the program. This change would ensure stable coverage for kids, even as their families’ income fluctuates.

The bill still includes $150 billion to expand home- and community-based Medicaid services for elderly and disabled people, down from the $400 billion Biden originally requested. The funding will raise wages for those homecare workers, hopefully growing that workforce and thus shortening the waiting list for these services. The federal government provides matching funds to states for these home- and community-based services, and the bill bumps that matching rate up permanently by 6%. The goal is to have all states provide these services outside of institutions, so that people who can be cared for in their homes don’t have to go to nursing homes because it’s the only option available.

It’s still possible that the loss of vision and dental coverage in a Medicare expansion provision will be picked up partially by making that coverage mandatory under Medicaid. That would still leave some elderly people out of coverage—those who don’t qualify for Medicaid but can’t afford the private coverage for those services. But low-income elderly people would have it, so that’s better than what we’ve got now. Coverage for hearing services in Medicare has survived so far, beginning in 2024 and paying for audiology examinations and hearing aids once every five years.

There are a number of other provisions, like bits of funding for pandemic preparedness ($3 billion); to build up the public health workforce ($7 billion); to increase the palliative care and hospice workforce ($100 million); and a few billion for grant programs for building, and capital projects for public health programs and community health centers.

Charles Gaba (our own brainwrap) has extensive section-by-section reporting on the bill and its health provisions as it stood as of the weekend. Some of that—the Medicare, Medicaid, and prescription drug pieces—are the most subject to change. Assuming Joe Manchin hasn’t blown the whole thing to smithereens.