Food insecurity did not increase in the pandemic, proof that we can afford to save the country

There are many lessons to learn from things like a global pandemic, and here’s a huge one: it is within the government’s capacity to make people’s lives better on a huge scale. As horrifying as this pandemic has been and continues to be, it could have been much, much worse without the provided help. Remarkably, food insecurity did not increase during the pandemic.

The Economic Research Service, part of the Department of Agriculture, released its food security report for 2020, finding that “an estimated 89.5 percent of U.S. households were food secure throughout the entire year in 2020, with access at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life for all household members.” That’s great—here’s the remarkable part for a public health and economic crisis: “The remaining households (10.5 percent, unchanged from 10.5 percent in 2019) were food insecure at least sometime during the year, including 3.9 percent with very low food security (not significantly different from 4.1 percent in 2019).”

Hunger—still way too high for the wealthiest country in the world—did not increase from pre-pandemic levels. At least in terms of raw numbers—it did increase amount households with children, among Black households, and in the South. All the communities hit hardest by the pandemic were also hit hardest by food insecurity, which indicates that more could have been done to secure the safety net for all Americans.

The achievement was still significant, however. “This is huge news—it shows you how much of a buffer we had from an expanded safety net,” Elaine Waxman, who researches hunger at the Urban Institute in Washington, told The New York Times. “There was no scenario in March of 2020 where I thought food insecurity would stay flat for the year. The fact that it did is extraordinary.” Compared to the Great Recession of 2008, it’s particularly striking, with 13 million more people becoming food insecure from the previous year. At the peak of the recession, 50.2 million Americans didn’t have enough food; it was 38.3 million in 2020.

Solving hunger altogether would have been better, yes. Spending $10 trillion in COVID relief—properly applied as in monthly checks to everyone—could have done the trick of keeping businesses afloat, people in their homes, and food on everyone’s tables. But as much as Congress did do demonstrates just what a difference an activist government can do even under the false constraints of deficit concerns.

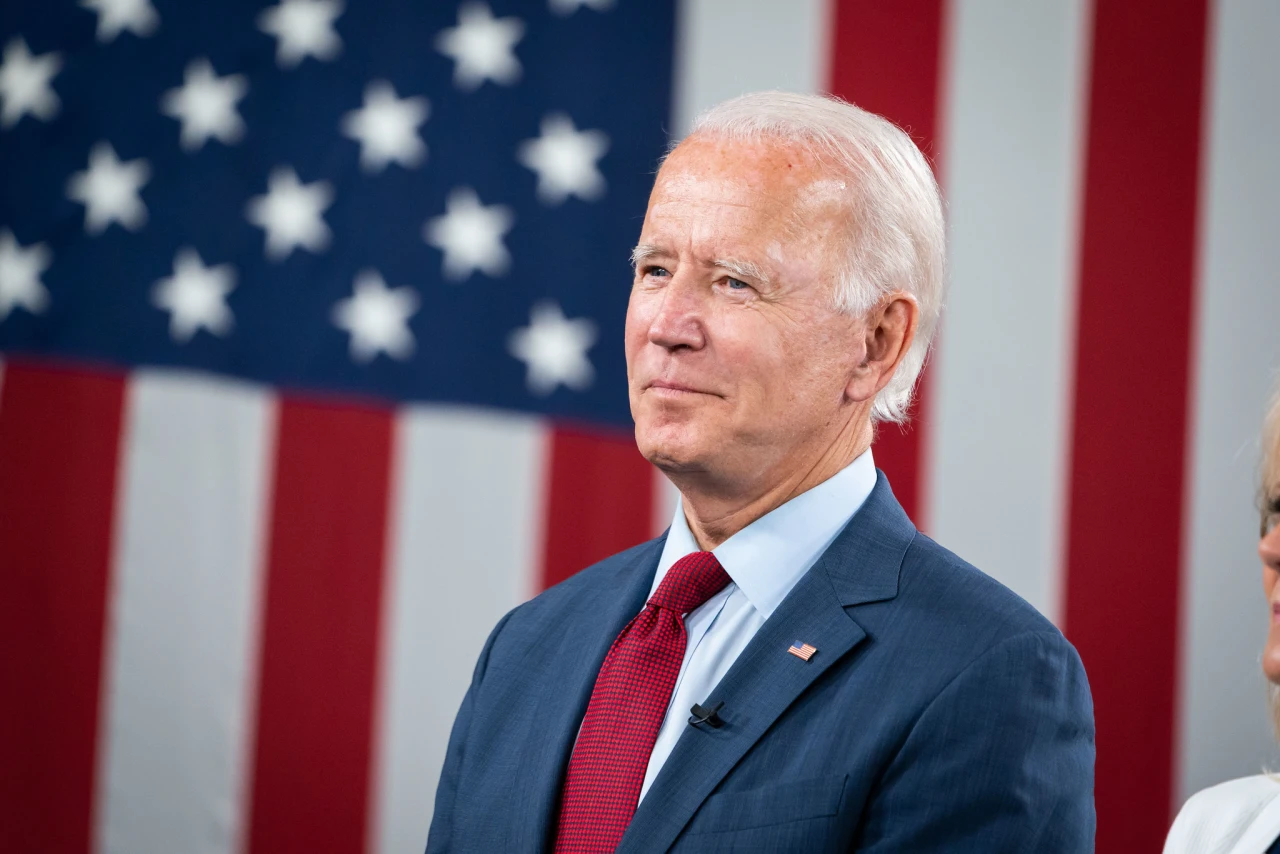

Speaking of which, this is something regarding the current $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill that comprises President Biden’s big jobs and economic improvement act that hasn’t been made clear enough, certainly by me. That $3.5 trillion that everyone is talking about as a huge scary number is spread out over the next ten years.

Over ten years, that’s hardly any money to spend on the truly transformative things Biden has envisioned. Could hunger go away entirely if families with young children get free pre-K? If college students don’t have to pay tuition? If home healthcare workers are earning a living wage? If new, living-wage jobs in new green industries flourish? Yeah. Hunger could essentially go away.

That money wouldn’t be hard to find, either. That the $3.5 trillion in investment over the next ten years is exactly half of what the wealthiest 1% of tax cheats have robbed the nation of in the past ten years. That’s not counting the 2017 GOP tax scam and the big breaks they got. That’s the taxes they have been obligated to pay and have been cheating us out of.

We can have nice things. The CARES Act and the American Rescue Plan showed that and did the job of keeping people fed. Making sure that all American people have nice things should be the priority over making Joe Manchin fossil fuel lobbyist friends happy.