Study: Food assistance falls far short of meeting the needs of America's food insecure

Congress stepped up for food insecure people in this pandemic, boosting Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) funds by 15%. But that still left hungry people in 41% of U.S. counties where SNAP benefits fall short in covering the cost of meals by nearly 50 cents per meal. The boost to the program from the COVID-19 relief bills expires on Sept. 30, when the nation presumably goes back to the status quo pre-pandemic and when the maximum benefit in SNAP will fall short of low-income meal costs in 96% of counties. That’s what a new analysis from the Urban Institute finds.

The average cost of a low-income meal, the Urban Institute estimates, is $2.41. The maximum SNAP benefit per meal is $1.97. Nationally, they find, “the maximum SNAP benefit fell short of meeting monthly low-income meal costs by $39.99 per person. Among the 10 percent of counties with the highest average meal costs, the monthly shortfall is $69.75 per person.” That’s before the pandemic boost—the status quo that we’ll return to in five weeks.

“Our findings show the maximum SNAP benefit still leaves a gap in covering the cost of food for many families with low-incomes,” Elaine Waxman, senior fellow at the Urban Institute, said in prepared remarks. “About 4 in 10 households receiving SNAP have zero net income—if SNAP does not cover the cost of a meal, people in such households will be at high risk of experiencing food insecurity. Additional consideration of the geographic variation in food prices when setting SNAP benefit levels is critical to the health and well-being of the most vulnerable communities.” SNAP benefits are the same across the mainland U.S., whether in New York or Huntsville, Alabama—the least expensive place to live in the U.S.

In New York, the gap between the maximum SNAP benefit and how much a cheap meal costs is $1.73 per meal—even with the expiring 15% benefit increase. On average across the country, the boosted benefits are 13 cents short of a meal cost. Despite the bump in benefits, reports of food insecurity have remained much higher than pre-pandemic levels.

The last time the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) calculated the cost of adequately nutritious food as a basis for SNAP benefits was 2006. According to Bureau of Labor Statics data, food prices in 2021 are 39.84% higher than 2006, with an average inflation rate of 2.26% every year of the past fifteen years. A bag of groceries that cost $20 in 2006 would cost $27.97 today.

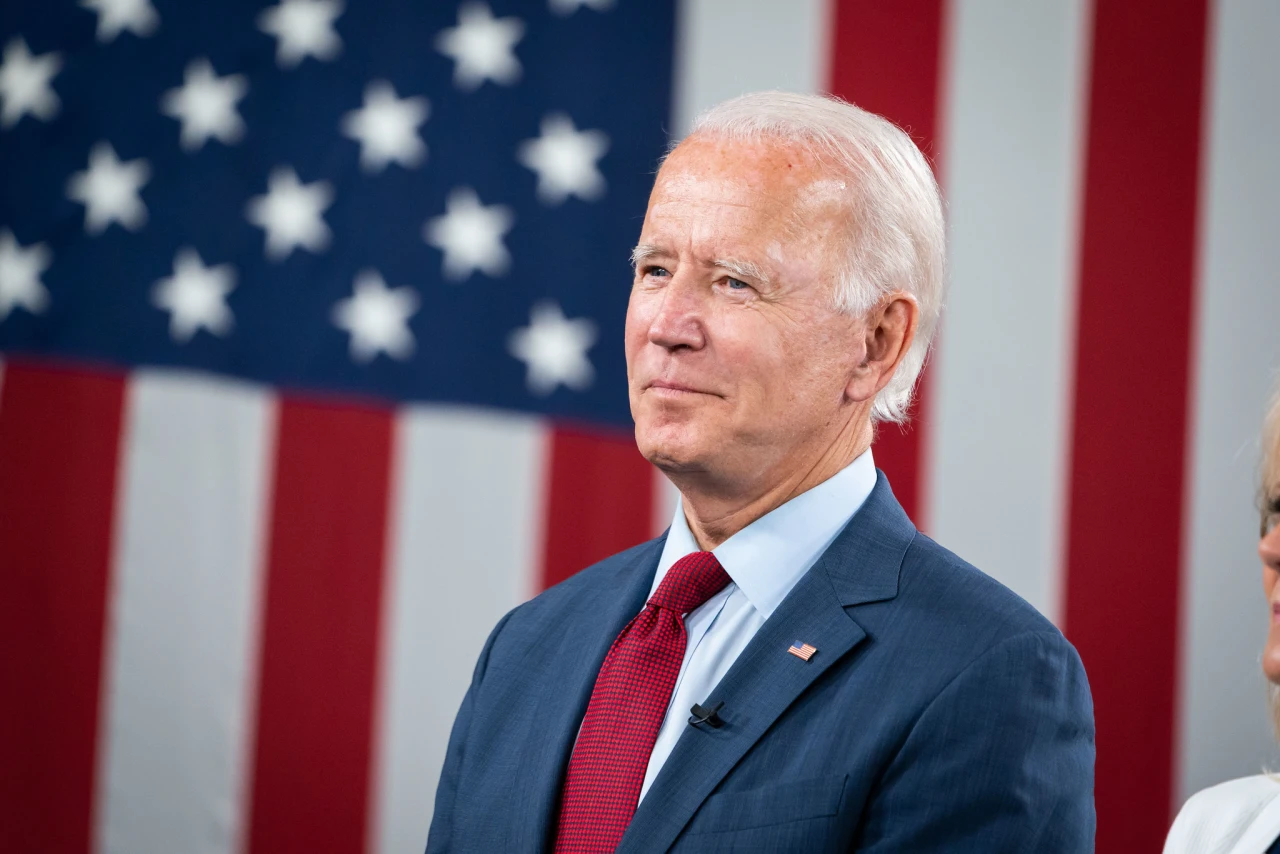

The 2018 Farm Bill did mandate a reevaluation of the Thrifty Food Plan (TFP), the USDA’s menu for a nutritionally adequate diet, and that’s supposed to be completed by 2022. In one of his first executive actions, President Joe Biden asked the USDA to “consider beginning the process of revising the Thrifty Food Plan to better reflect the modern cost of a healthy basic diet.”

“More than 40 million Americans count on SNAP to help put food on the table,” the White House pointed out in that order. “Currently, however, USDA’s Thrifty Food Plan, the basis for determining SNAP benefits, is out of date with the economic realities most struggling households face when trying to buy and prepare healthy food. As a result, the benefits fall short of what a healthy, adequate diet costs for many households.”

It’s not just the costs of meals, as the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) points out, but whether the TFP meets the nutritional and dietary needs of all families. “In an effort to hold costs down,” CBPP says, “the food plan doesn’t meet all federal nutrition standards, includes only small quantities of some non-luxury healthy foods commonly eaten by U.S. households, and includes foods in amounts that most U.S. households do not consume—such as quantities of milk and legumes that are well in excess of what people eat.”

It also assumes that recipients have much more time—and access to kitchen facilities—to prepare meals than is reasonable. That includes planning meals, getting to and from the store, comparison shopping, and finally preparing the food. The current TFP assumes that people on SNAP will spend an average of 138 minutes per day preparing food. SNAP recipients actually spend about an average of 50 minutes a day procuring and prepping food. That’s compared to 36 minutes a day for other households. Time is a luxury that low-income households don’t have.

Biden’s USDA does recognize all this, releasing a study in June finding that nearly “nine out of 10 Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participants face barriers in providing their household with a healthy diet throughout the month.”

“The most common, reported by 61% of SNAP participants, is the cost of healthy foods,” the USDA found. “Participants who reported struggling to afford nutritious foods were more than twice as likely to experience food insecurity. Other barriers range from a lack of time to prepare meals from scratch (30%) to the need for transportation to the grocery store (19%) to no storage for fresh or cooked foods (14%).” The next TFP should be more realistic, and that’s good. But they’re still in the process of reevaluating it, and they’re not ready to implement a revamped program. With the 15% pandemic boost about to expire, that reevaluation needs to be accelerated.