How progressives talk about July 4 and our national history in the post-Trump presidency era

I always enjoy Meteor Blades’ post about July 4, which highlights Frederick Douglass’ iconic speech, “The Meaning of July 4th for the Negro,” delivered in Rochester, New York, in 1852. The speech described the alienation from July 4, and from America more broadly, that enslaved people and African Americans in general felt. Although the most often-quoted section discusses that sense of alienation, it is also important to remember Douglass’ conclusion to the speech:

Douglass remained optimistic about the future despite the reality that in 1852, the overwhelming majority of Black Americans were enslaved. President Obama gave a speech on June 30, 2008, called “The America We Love.” It wasn’t about the meaning of America for African Americans as a community, but what America meant to him as an individual. Colbert I. King of The Washington Post compared Obama’s remarks with Douglass’. King noted that Obama, even while running for president and having his patriotism questioned, did not whitewash America’s history by ignoring its misdeeds. Although as a boy he had expressed a childlike love of our country, his patriotism remained strong even as he learned more about and gained a fuller understanding of our past:

King then neatly summarized the differences between Douglass’ and Obama’s speeches:

My guess, especially given his hopeful conclusion, is that if Douglass were alive today he would speak about America in a way that resembles Obama’s depiction—in the body of his public remarks over 25 years—in the broadest sense.

Neither would ignore the horrific crimes of the past, nor the way the legacy of those crimes continues to resonate. Neither would shrink from highlighting the continuing, fresh injustices being visited on African Americans. These injustices range from the killings by police officers of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, and so many others to continued discrimination in areas like home-buying—the primary way households build wealth—to those carried out by the Trump administration as well as by local authorities.

Neither Douglass nor Obama would ignore the systemic racism that permeates our institutions. Both would, however, present a nuanced narrative—one full of struggle and loss, yet also one of hope and the gradual progress toward a goal for which we continue to strive. In The Audacity of Hope, Obama asserted that on civil rights “things have gotten better,” yet he added that “better isn‘t good enough.” Both of those points are key.

We face serious, urgent problems today because of the white supremacy and anti-Blackness that still hold sway throughout our society. But to deny that things are better for African Americans in 2021 than they were in 1921—during the depths of Jim Crow, an era when hundreds could be massacred and great wealth destroyed by white rioters and murderers with impunity in Tulsa over a single 24-hour period, to name one out of countless brutally violent examples; or in 1821, when millions were in bondage—is not only incorrect, it is an insult to the people who fought, bled, and died over the decades in order to make things better.

Just last June, as Black Lives Matter protests marched through the streets of our cities and even smaller towns for days on end, the 44th president offered this take as part of a larger post entitled “How to Make this Moment the Turning Point for Real Change”:

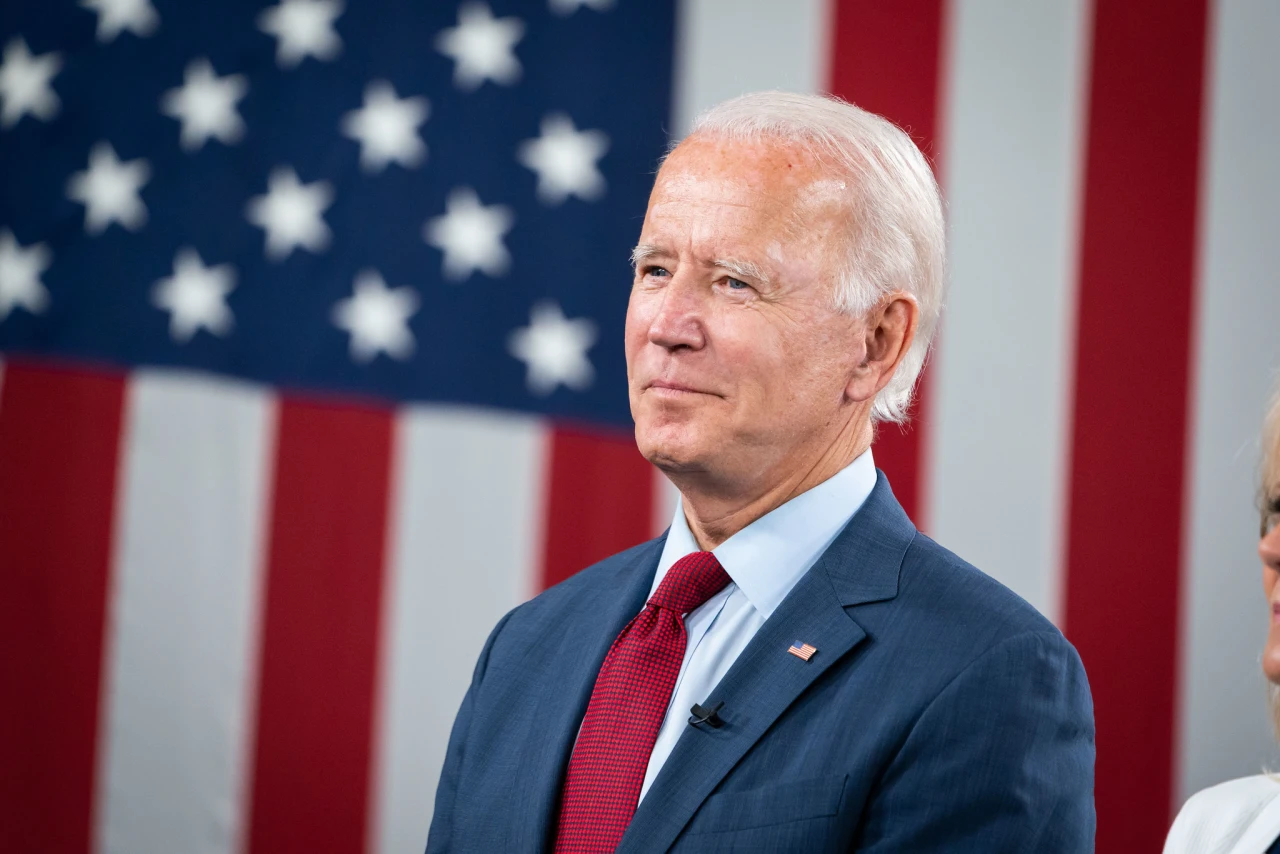

President Joe Biden, Obama’s one-time running mate, spoke in similarly balanced, yet hopeful terms about our nation’s centuries-long struggle to overcome our own racism in light of the historic events taking place in recent weeks:

And here’s Biden six months ago, in his inaugural address, where he rightly emphasized that we may never convince every American to come over to our side, but we can still prevail if “enough of us” do:

The battle is perennial. Victory is never assured. Through the Civil War, the Great Depression, World War, 9/11, through struggle, sacrifice, and setbacks, our “better angels” have always prevailed. In each of these moments, enough of us came together to carry all of us forward.

Meteor Blades is right to identify Frederick Douglass as a hero. Along a similar vein, Michael Lind characterized him in The Next American Nation as “perhaps the greatest American of any race, of any century.” It’s highly appropriate in 2021 to remember Douglass’ 1852 speech, especially on July 4. I want to reinforce that here. What I am also doing here is using Meteor Blades’ post about Douglass as a jumping-off point for a related—but different—discussion.

From a strategic perspective, politicians and public figures on the left have to be wary of allowing their rhetoric over an extended period of time to focus solely or overwhelmingly on feelings of alienation from this country. I’m not trying to tell anyone how they should feel. No one should do that. This is about what people publish and proclaim, and the strategic value thereof. What liberals cannot do, what Douglass himself did not do (as seen in the conclusion to his 1852 speech) is cede patriotism and an embrace of America to Trump and the right wing. This is a crucial point I’ve written about previously:

Lind wrote further about the importance of embracing an inclusive, singular national narrative of our country’s history with which Americans of every background can identify:

Even in writing this, I want to be crystal clear about what I’m saying so that nothing is misconstrued. I’m emphatically not saying that Meteor Blades or anyone else should tone down their criticisms of this country’s flaws or injustices, whether in the present or the past. To be more specific, I am not saying that Black or brown or LGBTQ+ Americans, or anyone who is marginalized, should keep their thoughts to themselves because they might scare the straight, white, Christian folks. I’m talking primarily about what progressive politicians and campaigns should say, what message they should emphasize.

We must find a way to do what needs doing, to shine a light on the problems and injustices in our country, while still publicly embracing a commitment to the whole country, the whole community. We have to do both of those things at the same time, over and over again, in order to get our point across and persuade people to join our movement. If we don’t do that, we can’t solve those problems and fix those injustices because, over time, we’ll lose elections and be shut out of power.

Democrats cannot win elections and make the changes that need making if the only people our broad vision of America’s story speaks to are liberals—and although the percentage of Americans who identify as such rose steadily from the early 1990s through the mid-2010s according to Gallup, it has remained stuck at around a quarter since then. We must craft a story that resonates enough—not necessarily 100%, but enough—to earn the support of most moderates along with liberals, two groups who together constitute a decisive 60% majority. Again, this isn’t about policy, or even compromise at all. We have to talk about our country in a way that doesn’t alienate people before they even hear our policies.

As politically engaged progressives, we know that this country can and must do better on a whole host of different fronts, that we need to enact systemic and fundamental change, and that in order to do so we need to understand our history in full. A history, however, that emphasizes only our crimes and ignores the progress is but the mirror image of one that does the opposite—one that, as Trump did at Mt. Rushmore on July 4, 2020, solely bathes our history in glory and righteousness. And if those are the only two options, many middle-of-the-road Americans, in particular whites but others as well, are likely to be more attracted to the Pollyanna-ish view simply because it sounds more familiar and makes them feel better.

As survey data from the Public Religion Research Institute makes clear, Donald Trump certainly appeals to those who are likely attracted to such a view, those who see America as having veered away from what once made it “great.” As Ronald Brownstein explained in 2016, “Trump’s emergence represents a triumph for the most ardent elements in the GOP’s ‘coalition of restoration,’ voters who are resistant to demographic change.” This is certainly just as true now as it was five years ago. Why else would Trump present himself as the most powerful defender of Confederate monuments?

Progressive politicians and campaigns have to make sure to present a balanced and truthful picture. That’s the most effective way to get those people who sometimes forget about the crimes our country has committed to remember them and to work toward reversing their effects, rather than dismiss liberal criticisms as somehow “anti-American” because liberals supposedly talk only about the negatives. Progressives have to present our case as representing the true American values, and contrast them to the values of those whom we oppose, as Obama and Joe Biden did in their condemnations of Trump’s family separation policy, for example. Inclusion, equal rights, and a strong sense of national community that nurtures bonds connecting Americans of every background is what makes America great, not fearmongering about immigrants.

The Man Who Lost Lost An Election And Tried To Steal It had his ridiculous July 4 event at Mt. Rushmore last summer, but we must not allow his twisted definition of American greatness to go unchallenged. (And please check out Meteor Blades’ post on that event—which he brilliantly characterized as “our corrupt and conniving president, who has so many times proved he despises American Indians, showing up to fluff his patriotic feathers at a commercial enterprise built on land stolen from the Lakota nearly a century and a half ago using starvation tactics and gunpowder.”)

Compare what the twice impeached former president said last July 4 to what the man who beat him by 7 million votes said on that same day, remarks that Daily Kos’ Jessica Sutherland aptly called “the ‘presidential’ Fourth of July address America deserves,” struck a similarly balanced note. The vice president showed how progressives can define celebrating the July 4 holiday in a way that, hopefully, works for all Americans, including members of marginalized groups.

The video is only about 90 seconds long, and I urge you to listen to the whole thing, both for the content and for the passion with which Vice President Biden delivered it. At the heart of the statement is how we talk about our history. Again, Biden didn’t tiptoe around the uncomfortable truth. For example, Biden cited Jefferson’s ownership of human beings, and our country’s discrimination against women—while also emphasizing that putting those all-important words “all men are created equal” down on paper provided support for those fighting to help America become the place we have long aspired to be.

As for how that history connects to our future, Biden added: “We have a chance now, to give the marginalized, the demonized, the isolated, the oppressed, a full share of the American dream. We have a chance to rip the roots of systemic racism out of this country. We have a chance to live up to the words that founded this nation.”

On our country’s birthday last year, only one of the two candidates for president gave us a story of our past that will enable us to craft a viable journey forward, because only one of their stories told the truth. Biden acknowledged our struggles to put into practice the worthy ideals our founders laid down in 1776, and demands a future where we make them fully and finally real for every American. The results last November provide evidence that Biden’s position is one that far more Americans can identify with than Trump’s.

Ultimately, as a people, we require for our survival a story of our country that reflects the full, balanced truth of our past, one that Americans of every background can feel includes them. President Barack Obama has offered that sort of historical narrative throughout his public life, and Biden has been doing the same thing, in particular since he began his 2020 campaign. Trump, on the other hand, offers nothing but hate—because he’s the one who seeks indoctrination. Historian Jill Lepore wrote in 2019 about the danger of leaving the crafting of a unifying national narrative to those who would use history to divide us. “They’ll call themselves ‘nationalists,”’ she wrote. “Their history will be a fiction. They will say that they alone love this country. They will be wrong.”

People need to feel a sense of belonging, a sense of identity, something that connects them to a purpose larger than themselves. A progressive concept of Americanness that can connect Americans to one another across boundaries is crucial to countering Trumpism broadly, and white nationalism specifically. I’ve written previously about women of color like Nikole Hannah-Jones, Rep. Ilhan Omar, and our country’s first youth poet laureate, Amanda Gorman, who have spoken about their concept of patriotism—one that connects powerfully with progressive values on matters such as racial justice. Look at how Hannah-Jones talked about our history in her Pulitzer Prize-winning introductory essay to The 1619 Project, where she summed up so much in a short paragraph:

Those who have fought for equality have long sought to connect that idea to America’s fundamental principles, to our own history. Frederick Douglass did it, even in the speech discussed above, as did the Black abolitionist David Walker a generation earlier, who called on us to “[h]ear your languages, proclaimed to the world, July 4th, 1776.” The Declaration of Sentiments—the manifesto signed by those who gathered in Seneca Falls in 1848 to demand equal rights for women—began by taking the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence, which eloquently declares the equality of all men, and modifying it by adding two key words: “and women.”

Martin Luther King Jr. also rooted the principles for which he fought squarely within, rather than in opposition to, basic American ideals. We see this in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” where he predicted that the civil rights movement would succeed because “the goal of America is freedom,” and in his “I Have a Dream” speech, in which he proclaimed that the dream he described that day was “deeply rooted in the American dream.” So did Harvey Milk when he said: “All men are created equal. Now matter how hard they try, they can never erase those words. That is what America is about.” So did Barbara Jordan, who noted: “What the people want is simple. They want an America as good as its promise.”

Finally, Barack Obama did something very similar in Selma at the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Bloody Sunday March, when he identified those who walked and bled on that bridge as the ones who truly represented what America is supposed to be:

Progressives must criticize. That is crucial. We must also tell the truth, both about the present and the past—as Joe Biden did speaking to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the aforementioned Tulsa Race Massacre. Additionally, we must inspire, because inspiration is how we motivate action. We can and must use the story of our country, which above all is one of brave people fighting—often against more powerful people and institutions in our country—to make this a better, fairer, more just place for all Americans. That fight to make America truly great inspires me, and I hope it inspires you as well.

[This is a revised and updated version of an essay I have posted previously on July 4, with some material revised and added from a post that discussed Biden’s speech from July 4, 2020.]

Ian Reifowitz is the author of The Tribalization of Politics: How Rush Limbaugh’s Race-Baiting Rhetoric on the Obama Presidency Paved the Way for Trump (Foreword by Markos Moulitsas)