Nevada becomes second state to add a public option to health insurance exchange

On Wednesday, Nevada Gov. Steve Sisolak, a Democrat, signed legislation creating a public health insurance option for the state’s marketplace, joining Washington State as the only two states to offer a public plan. The move could expand coverage to the 350,000 uninsured Nevada residents, and lower the cost of health insurance overall on the market.

The state will require the three insurers in the state—Centene, UnitedHealthcare, and Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield—which provide managed care organizations for the state’s Medicaid program to bid for managing the program “as a condition of continued participation in any Medicaid managed care program,” said Democratic state senator and Nevada’s majority leader, Nicole Cannizzaro. The premiums for the public option will at the outset be set 5% lower than the “benchmark” plan—the plan the state uses to define essential health benefits for individual/family and small group plans—with an eventual goal of having premiums 15% lower than the benchmark. The public option will be either a silver-level plan covering 70% of medical costs, or a gold-level plan that covers 80% of costs. Health care providers that accept patients through Medicaid and/or the state employees health insurance plan will be required to see public option patients.

Coverage won’t begin until 2026, and the state has to apply for a waiver with the federal government to get final approval. The Affordable Care Act gives states the leeway to create public options on their exchanges, but the details have to be approved by the federal government.

Cannizzaro spoke with Vox’s Dylan Scott before the bill passed, stressing that they don’t want to punish providers at all with this law, so they did not set payment rates in it. They did, however, set a floor—the public option will have to pay at least what Medicare pays in reimbursements or better. “What we are trying with the language in the bill was to ensure that it would be at least Medicare or better,” she said.

“We’re talking about getting people who otherwise are costing the system a lot of money in their care … into a place where they can have consistent, ongoing, preventative health care and the speedy and remedy treatment of any more acute problems that come along, so we don’t have them showing up in emergency rooms with a whole host of issues that have been ongoing yet unable to be addressed because of that lack of access to health care,” she said. Which has been the goal of health care reform from the outset, going back to the failed efforts of the Clinton administration back in the 1990s.

“There is still this population that is not being served by what we currently have—not employer-based plans, not the exchange, not Medicaid,” Cannizzaro said. “If we can lower premiums, that would incentivize and bring people onto the public option. So that’s really where we decided that we would implement the 5 percent, and then 15 percent over four years.”

That’s the vision for the public option many had for Obamacare, a vision that was squelched by health insurers and other stakeholders back in 2010. The same stakeholders tried to kill it in Nevada, too. “The public option provisions of the bill are neither a solution nor a benefit to Nevadans,” providers, hospitals, and insurers wrote in a May 31 letter Sisolak, asking him to veto it. They said that the legislation would “add costs, increase burdens and damage both the health insurance market and health care provider network.”

Sisolak rejected those arguments. “While we have weathered the storm together with our battle-born spirit, COVID has exposed the fact that our state must strengthen our public health infrastructure,” Sisolak said Wednesday as he signed the bill. “Today, we’re taking steps to do just that by signing three bills into law that help us to move forward as a stronger, healthier Nevada.” (One of the other bills he signed requires employers to give paid leave to workers for getting their COVID-19 vaccinations, and another which creates a Public Health Resource Office within the governor’s office.)

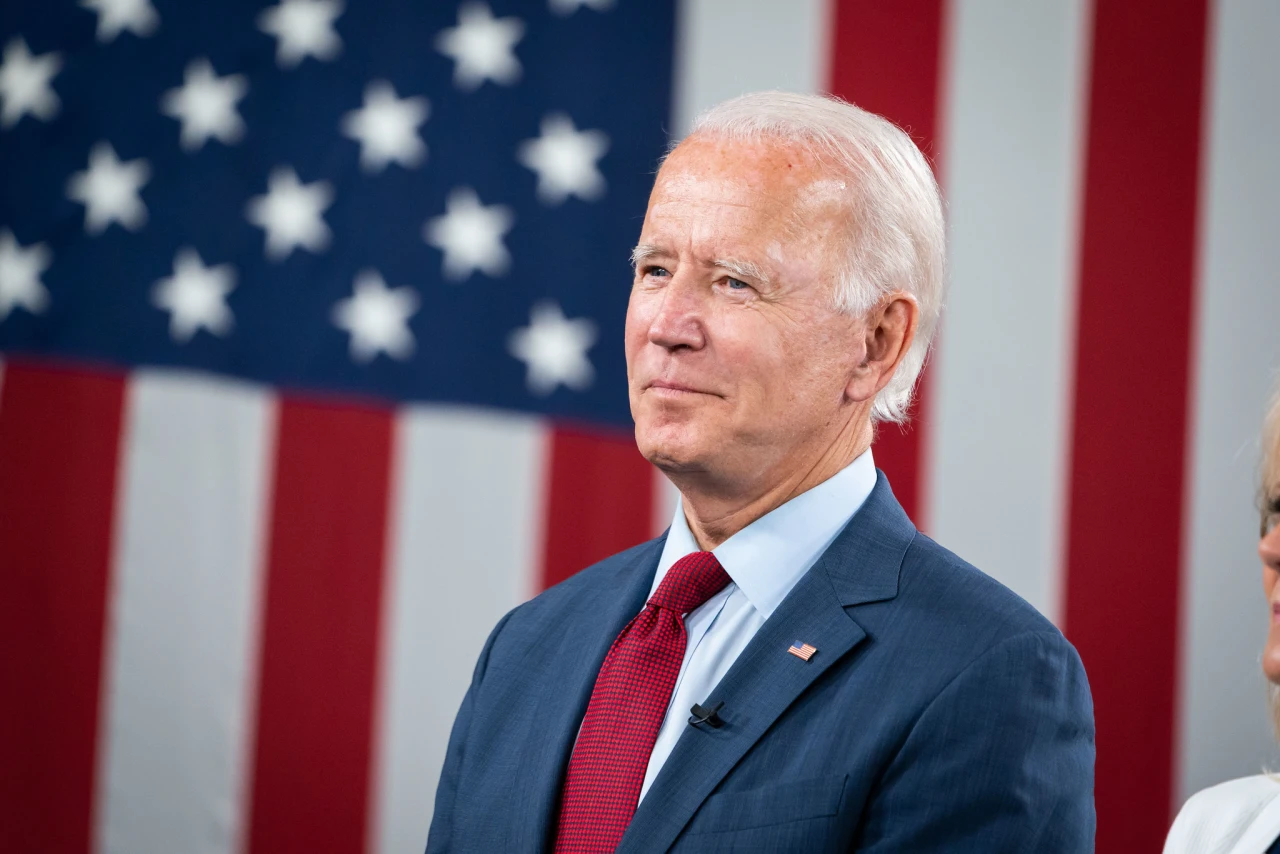

President Joe Biden campaigned on bringing the public option back and putting it on the marketplace nationwide, but that goal has been slipping. Washington State’s effort has been mixed so far. Fewer than 2,000 people had signed up as of mid-January, and premiums haven’t been driven down on its exchange. Only 19 of the state’s 39 counties have a public option offering, with just five insurers in the state offering them.

With both states having private insurers operate the public options, they aren’t fully government-run as the idea of “public option” would suggest. “The lesson is this stuff is complicated,” said Sabrina Corlette, co-director of the Center on Health Insurance Reforms at Georgetown University. “The dynamics between payers and providers are not always easy to direct from a state level.” Nevertheless, more states including Oregon and Colorado are exploring ways to implement them.

Billy Wynne, a health care consultant and founder of the Public Option Institute, believes that these efforts “show that the Biden administration is going to need to respond to this appetite among the states to implement public option programs with federal support.” Biden had a public option in his campaign health care proposals, promising “the choice to purchase a public health insurance option like Medicare. As in Medicare, the Biden public option will reduce costs for patients by negotiating lower prices from hospitals and other health care providers.”

That’s not happening, at least not right now. Biden’s proposed budget released last month included no provision for a public option, though it did call on Congress to “take action” this year to reduce prescription drug costs and “to further expand and improve health coverage.” The proposal included support for a public option, as well as for lowering the Medicare eligibility age and expanding Medicare coverage to include hearing, vision, and dental. But the administration didn’t provide any details for how that should happen or include specific funding for any of it.