We have a Supreme Court problem and a Senate problem, and 'deluded institutionalists' make it worse

Sen. Susan Collins must be feeling at least a tiny bit concerned right about now if she’s at all capable of considering the consequences of her actions anymore. After all, she staked her reputation on the “promise” she secured from then-Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh that Roe v. Wade was "settled law,“ with “precedent upon precedent.”

And here we are now, with the Supreme Court poised to consider a Mississippi abortion law passed for the express purpose of getting the Supreme Court to further erode abortion rights.

For eight months, the court had been sitting on this case. Eight months during which a liberal stalwart on the court died and a far-right, inexperienced ideologue took her place. The arrival of Amy Coney Barrett on the court in Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s seat has sealed the conservative majority. That’s after the arrival of Kavanaugh, another far-right partisan who got there because of Collins’ vote. Kavanaugh wasted little time in showing his true hand on abortion, dissenting in the case of June Medical Service vs. Russo and voting to overturn four years of precedent regarding reproductive choice.

After eight months of testing the wind, the court’s conservative majority has now decided to flex its muscles, and abortion is on the docket.

The same day the court announced it’s taking up the case, the Harvard University Press previewed an upcoming offering from Justice Stephen Breyer, the 82-year-old justice who has been lately defending the Supreme Court against the calls for court reforms. “A growing chorus of officials and commentators argues that the Supreme Court has become too political,” the press release announcing the book intones.

As if the Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett confirmations weren’t intended to give the far-right the judicial outcomes it’s been investing so much dark money in.

The release also announces the book is coming from “sitting” Justice Breyer in September, meaning he’s intending to hold out to the bitter end, arguing that “public trust would be eroded by political intervention, dashing the authority of the Court.” As if the Court held the public trust. As if the body politic didn’t view the court as a political entity after Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell unscrupulously and ideologically packed it already.

Breyer was there for all that. He was there when McConnell held the Scalia seat open for nearly a year after his death, refusing to allow President Obama to fill it. He was there when McConnell dropped the filibuster on Supreme Court nominees so he could rush Neil Gorsuch on to it. He was there when McConnell’s Republican Senate rushed Kavanaugh onto the court despite credible allegations of sexual assault against him as well as lingering big questions about his truthfulness with the committee in confirmation hearings, and how he experienced a timely and favorable reversal of fortunes in his personal finances, wiping out years of very large debts. He was there when McConnell sped Barrett onto the court just weeks before a presidential election, in complete contradiction to the excuse he used for keeping Obama’s nominee, Merrick Garland, off the court.

That Breyer actually thinks the American public saw all that happen and doesn’t question the legitimacy of the court is a problem. It makes him, as The Washington Post's Paul Waldman puts it, a “deluded institutionalist,” a “solitary institutionalist, so convinced that he alone can save the body to which he is devoted that he blinds himself to reality and helps those who would undermine everything he supposedly stands for.”

Waldman equates what Breyer is doing with the court with what Joe Manchin is doing with the Senate: protecting an institution “that now exists only in his imagination.” That’s the Senate of Manchin’s fever dreams in which Susan Collins acts in good faith. We’ve already seen where that gets us.

Both institutions, the court and the Senate, have to be reformed, and one can’t be done without the other. Yes, there needs to be an expansion of the court to dilute the politicized poison that threatens to consume it. And yes, there needs to be a reform in the Senate to break the minoritarian rule that is threatening, well, everything.

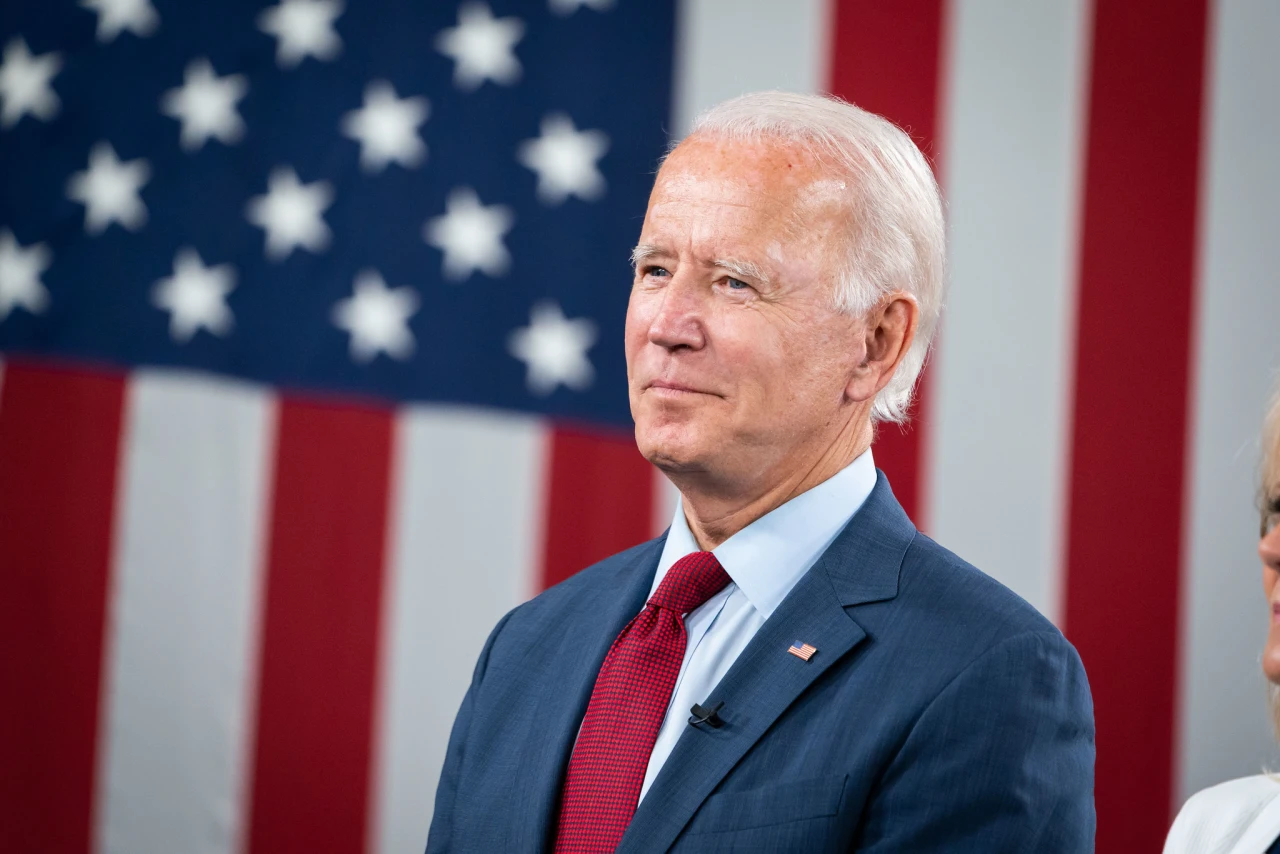

Biden’s special commission, which has been given six months to ponder these questions and which also includes some members very hostile to abortion rights, isn’t the solution. It isn’t going to save not just fundamental rights, but much of Biden’s agenda, which Republican states and Republican judges are primed to start challenging.

As for abortion rights, here’s the White House’s pat answer:

The problem is that abortion rights are not going to be codified by a 50-50 Senate. It’s not going to happen as long as the filibuster exists.