House Democrats united in pushing Biden to expand Medicare

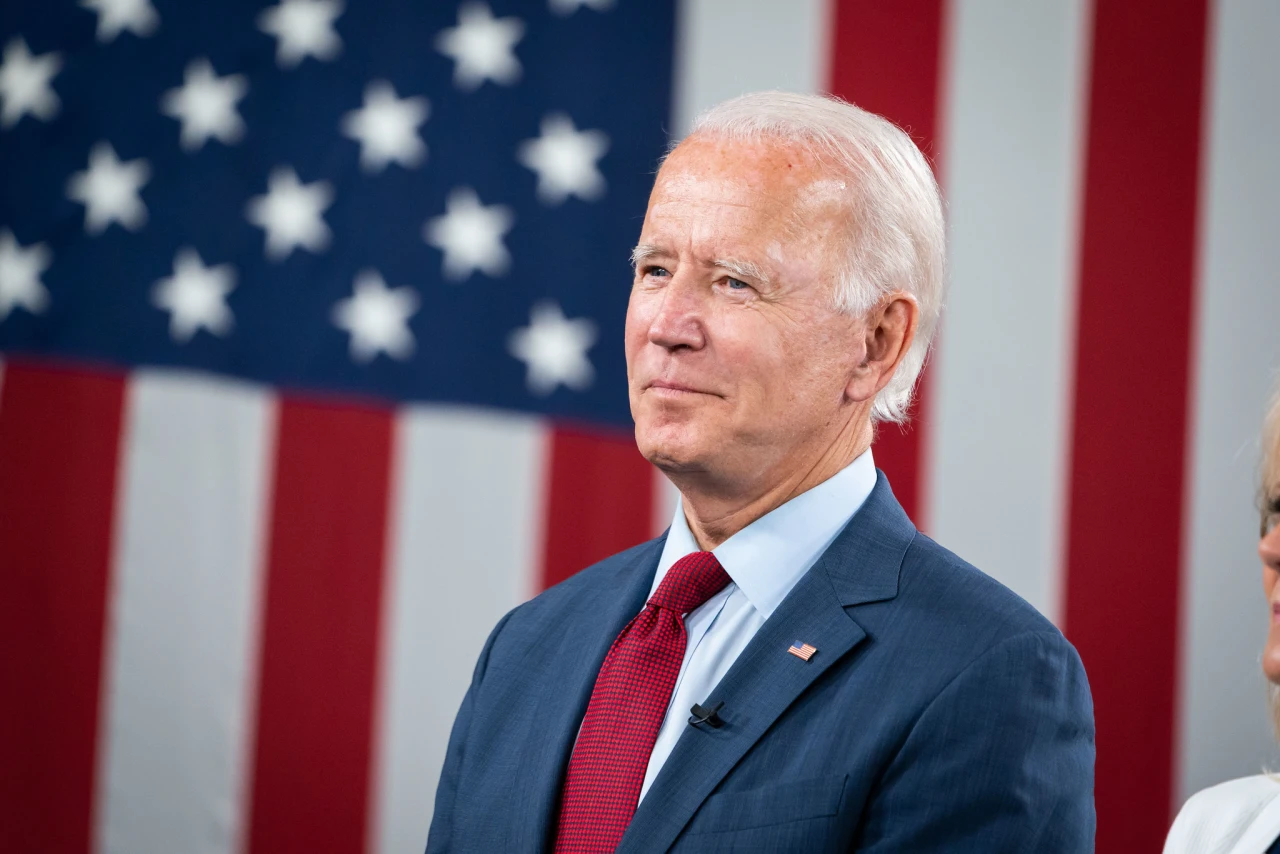

President Joe Biden is expected to unveil a $6 trillion budget for 2022 on Friday. Sources for The Washington Post say that there are no new major policy initiatives in it, but that it will include the proposals Biden has already unveiled, including the $2.3 trillion American Jobs Plan for infrastructure and the follow-on American Family Plan at $1.8 trillion.

It will also include a call for Congress to do two things: create a public health care option on the Affordable Care Act exchanges, and lower the eligibility age for Medicare to 60. But what the budget proposal won’t do is advance any specific policies for doing that or earmark any specific funds for it. Congress needs to do it, the budget will say. The Democratic Congress in return is telling Biden, in essence, to help them pass it by including it in infrastructure.

It’s not the whole of the House Democrats, but almost. More than 150 of them, from Rep. Pramila Jayapal of Washington State—the chair of the Progressive Caucus—to Maine’s Rep. Jared Golden, the only Democrat to vote against the American Rescue Plan, the massive and essential COVID-19 relief bill. He justified that vote, by the way, by saying: “Borrowing and spending hundreds of billions more in excess of meeting the most urgent needs poses a risk to both our economic recovery and the priorities I would like to work with the Biden Administration to achieve, like rebuilding our nation’s infrastructure and fixing our broken and unaffordable healthcare system.”

So apparently he feels the need to now fix the broken and unaffordable healthcare system. Welcome aboard, Mr. Golden. He’s joined with about 70% of his colleagues to push this effort, which The New York Times says “promises will be a noisy and sustained campaign to pressure President Biden to include a major expansion of Medicare in his infrastructure package.”

“It is really unusual to get this level of intensity on a health care proposal,” Jayapal told the Times. That proposal is to lower the eligibility age for Medicare to 60 and expand coverage in the program to include vision, dental, and coverage for hearing aids. They propose paying for the 10-year, $350 billion cost by allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices. Jayapal estimates it could save $650 billion over 10 years, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) says more like $450 billion. Either way, the expansion would be paid for. Golden has noted that the Department of Veterans Affairs has that authority to negotiate prices, and according the General Accountability Office, in 2017 it paid an average of 54% less on prescription drugs than Medicare.

Democratic leadership has been more focused on making permanent the American Rescue Plan temporary provisions that have saved so many people so much money. But as Jayapal says, there is no reason not to do both and use all that Medicare negotiation drug prices money to pay for it.

Some in the group are pushing even further. Rep. Joe Neguse of Colorado believes the eligibility age should be lowered to 55, bringing in more than 40 million more people. He also advocates for making the benefits of Medicare much broader, pointing out how many seniors can’t afford dental care or hearing aids. “Many of our nation’s seniors are unable to receive care for their ailments because Medicare benefits are not as a broad as they should be,” he said.

“How crazy is it that we pay into Medicare all our working lives, and then at the time when you probably need dental care the most, Medicare doesn’t even cover it?” Golden said in a Times interview. “I know seniors are frustrated by that.”

There’s a move from a group of Democratic senators who introduced legislation last month to open up eligibility for Medicare starting at age 50. Ohio’s Sherrod Brown recalled one of his constituents in talking with reporters on the bill’s release. “I remember a few years ago, I was at a town hall meeting in Youngstown, Ohio, and a woman stood up and said ‘I’m 63 years old. My goal in life is to live ‘til I’m 65 so I can get on Medicare. My goal in life isn’t to take a trip to New York or be able to see my grandchildren,'” Brown said. “She was so focused on her health care. She had two jobs at the time, both low-wage jobs and neither provided insurance. She just knew how important it was to have insurance and get on something that is popular and important and sufficient and effective as Medicare.”

Lowering the Medicare age has proved popular with the population in general—about half of the public told a recent Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) poll they support adding to it, and 69% support the provisions in the American Rescue Plan that expanded federal subsidies for people to purchase plans.

Both ideas are also popular with employers. A survey from Purchaser Business Group on Health (PBGH) and KFF released at the end of April shows how desperate large employers are to have healthcare costs reduced, and to be relieved of the burden of providing them. The CEOs and top executives surveyed nearly unanimously—87% of them—“believe the cost of providing health benefits to employees will become unsustainable in the next five-to-10 years, and 85% expect the government will be required to intervene to provide coverage and contain costs.”

Their costs for family coverage on employer-sponsored coverage grew 55% in the past 10 years, increasing “at a rate at least twice that of both wages (27%) and inflation (19%).” Not only do the business leaders think government will have to intervene, “83% said such actions would be better for their business and 86% said these actions would be better for their employees.” And “[r]elatively few respondents generally disagreed with proposals that would lower the age of Medicare eligibility to age 60 or create a new public plan coverage option, either for their own employees or the general public.”

This is who Biden and the Democrats need to gear up for their campaign to expand coverage. “Any efforts to expand public coverage options or restrain prices will be met with strong opposition from the health care industry,” said Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at KFF and an author of the report. “Employers, who foot much of the nation’s health care bill, could be a powerful counterweight.”